6.4 A Painter, a Palette, a Paper, and a Magnifier

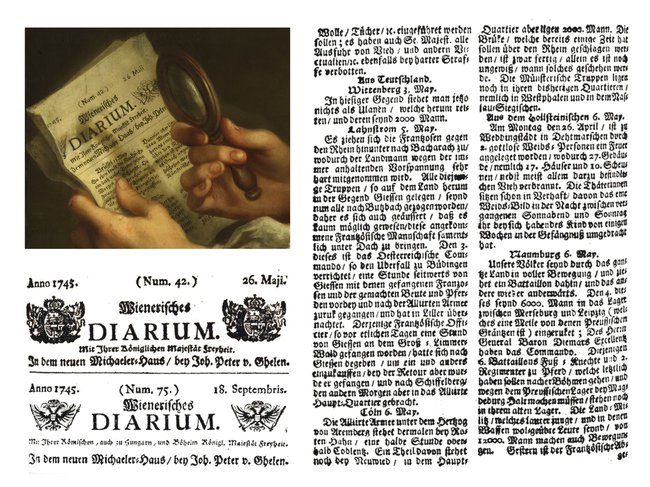

Seybold’s Self-Portrait with the ‘Wienerisches Diarium’ of 26 May 1745 and a Magnifier [42] has been published frequently by its curators, especially by Klára Garas in her seminal essay on Seybold from 1981, and recently in a study about the history of the Viennese periodical. According to Garas, the protagonist presents himself as a painter and a bourgeois in his homely plainness, with a local newspaper to stress the ‘social and cultural advancement’ of his trade and his ‘class development from craftsman and court servant to independent, educated and also intellectually active painter of the bourgeois revolution.’ In her view, Seybold immortalised himself with this rare attribute in order to emphasize his ‘intellectual and social standing’.1 Recent authors agree with Garas’s theory and add to the interpretation by expanding on her observations. Not only did Seybold provide his portrait with a terminus ante quem by depicting the newspaper with a date of publication, they argue, but also, by altering the coat of arms which flanks the title of the newspaper, he stressed the imperial credentials of the Wienerisches Diarium. In doing so, he referred to his own achievements in Dresden and Vienna. Moreover, the authors claim that by displaying the sentence ‘so eben lauft die Nachricht ein’ (the message has just arrived), Seybold underlines the actuality of both the medium and the portrait.2 Although this makes sense, this explanation of the presence of the newspaper leaves many questions unanswered, for example, why Seybold chose to depict this particular issue.3

Christian Ludwig von Hagedorn hit the nail on the head when he acknowledged the different styles in Seybold’s œuvre. However, he also described another important feature of his œuvre: ‘Ses figures à mi-corps sont autant de Portraits, mais, par la maniere [sic] de les historier, de vrais Tableaux’ (his half-length portraits are true paintings because of the way they are historized).4 When he wrote this, Hagedorn apparently had Seybold’s (predominantly genre-like) half-length figures in mind, since these works exhibit sufficient narrativity to compete with the high-ranking genre of history painting. Hagedorn thus considered them to be ‘vrais Tableaux’, as opposed to the less esteemed ‘blosse Bildnisse’.5 Art theory was in general clear about the standard that a portrait of quality should attain: the sitter had to be assigned with relevant attributes or depicted in an activity pertaining to his or her status, profession or age, but without exaggeration or compromising the likeness.6 As this self-portrait obviously purports to be more than a simple effigy of Seybold’s physical appearance, it might be possible to identify a form of ‘history’ within this composition. First of all, his appearance points strongly in the direction of Rembrandt as the chief example.

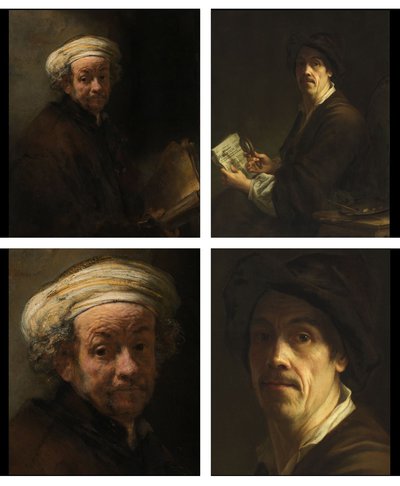

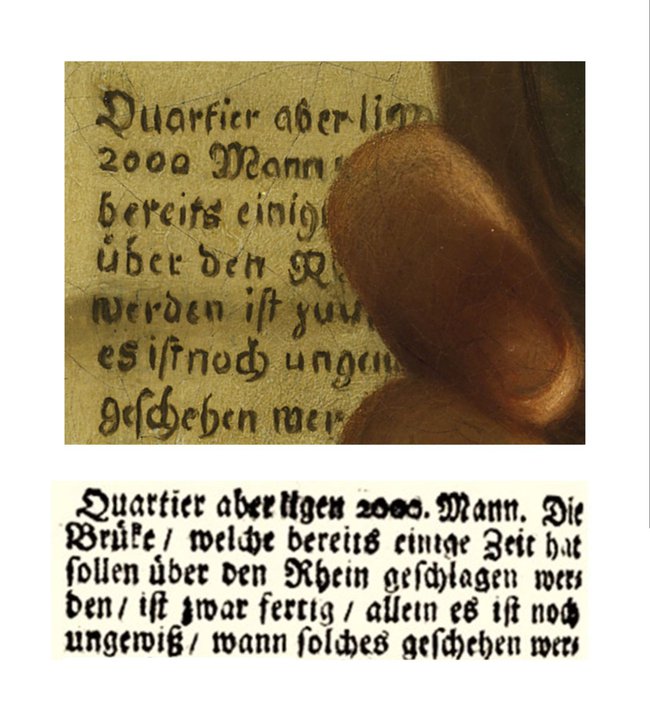

The pose of Seybold’s upper body and the distribution of light and shadow are comparable with Rembrandt’s etched Self-Portrait from 1633 [31], with both looking over their shoulder at the viewer, already a traditional motif for self-portraits [43]. It also seems to be dependent on Rembrandt’s large frontal Self-Portrait in the imperial collection [29], which shares profound similarities in costume and in its almost monochrome colour scheme. Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait in Amsterdam also enters the equation because of the similar pose (albeit in mirror image), the illusion of the artist being interrupted while reading, the fact that he is looking straight at the viewer, and his facial expression, with the raised and curved eyebrows and furrowed brow [44].7 In his Iconologia Cesare Ripa describes this expression of astonishment as a characteristic of the personification of the Art of Painting, Pittura, in which it represents the fathoming of the creative processes in the painter’s mind.8 In Seybold’s portrait, this inquisitive expression is reinforced by the magnifying glass focusing on the newspaper, aided by the distribution of light, which forcefully guides the viewer’s gaze towards the newspaper. Together with the direction in which the thinnest brush in the thumbhole of the palette is pointing, these visual directives invite the beholder to scrutinize the well-illuminated sheet of paper – on which the painted letters are actually too large for Seybold to require a magnifier, neither for reading nor for painting them.

To comprehend the full meaning of the newspaper’s content and its purpose in the portrait, it is necessary to transpose the fictional image from the painting into its historical setting. Thus, by comparing the realistic-looking newspaper excerpts with the painter’s biography, and by following the visual cues offered by the painting, its meaning can be deciphered. With his self-portrait, Seybold explicitly alludes to the Dutch master Rembrandt, as was already clear from the aforementioned analogies in iconographic motifs and style. However, he simultaneously and cleverly assumes the role of ‘court painter’, as can be deduced from subtly hidden clues. Moreover, every single one of these clues lives up to the historical reality of Seybold’s personal circumstances. Although the newspaper actually exists, it is not a slavish imitation of the actual issue [45]. The fact that the lettering has been enlarged, which does not correspond with the true size of the font, has been pointed out here already. The order in which the news items have been arranged in the newspaper do not correspond with the actual issue either: the reports depicted here are not on its front page, but are randomly printed elsewhere in the paper.9 The undated news item relates in reality to an item of 6 May 1745, a date that intentionally coincides with Seybold’s decretal appointment to the Dresden court. The painter thus advertises his confirmed and privileged new status of court painter at the Dresden court of King Friedrich August II (1696-1763), who, at that time, simultaneously ruled as Reichsvicar during the interregnum, since a new Emperor had not yet been chosen. This decree was signed by the King and his Minister of Culture, the aforementioned Count von Brühl. This royal employment is most likely also the reason why the beam of light passing through the magnifier especially highlights and delineates the text fragments ‘Mit Ihrer König[lichen]/ dem neuen Mich[aëler]’ and ‘So eben lauft [die Nachricht]’.10

The official title bestowed upon Seybold is once again emphasised by the Habsburg double eagle, flanking the painted newspaper’s title, which was not part of the imprint of the Wienerisches Diarium until after Francis Stephen (1708–1765) was elected Emperor later that same year. Only then did it replace Maria Theresa’s coat of arms.11 Although neither the date of the news item nor that of Seybold’s decree, 6 May 1745, is visible to beholders of the self-portrait, the relation between the date and the ratification of the appointment can hardly be coincidental. This deliberate ‘concealment’ of the date, which would have challenged a well-informed period viewer, forms a subtle, but ingeniously construed reference to the coveted status of court painter conferred to him by decree, to which emoluments and unalienable privileges were attached; though this position was not officially conferred upon him by the Viennese court until 16 July 1749, it was obviously hinted at by the double eagle in this portrait.

The image of Seybold as a ‘court painter’ imposes itself once again on the beholder thanks to the painter’s palette on the little side table [46]. With this motif, Seybold refers to Alexander the Great’s court painter Apelles, the role model par excellence for painters who aspired to elevate their status. Like other painters from antiquity, Apelles’s palette consisted only of four colours, white, yellow, red and black, which enabled him to paint convincing portraits.12 On the palette, however, there is no black paint, although one could argue that the colour is represented by the dark thumbhole and by the newspaper’s black printing ink, at which the aforementioned brush, balanced in the thumbhole, is pointing. Again, with this motif the viewer is encouraged to look at the paper.

Seybold’s self-fashioning as Rembrandt van Rijn and his imitation of the master are even further emphasised by the painted fragment which contains the words ‘über den R[hein]’, in which the river’s name ‘Rhein’ is partly hidden from view by his index finger, though the wording is known from the actual issue [47]. The intention for this phrase to be understood as a meaningful motif can also be deduced from the fact that the words ‘über den R[…]’ are underlined by the shadow of the paper’s horizontal fold. Although Rembrandt, from 1632 onwards, preferred to use only his first name, in imitation of Italian Renaissance Masters such as Titian and Raphael, he was also known internationally by his full name, which includes the toponym referring to the tributary of the river Rhine that flows through Rembrandt’s birthplace Leiden.13 Can ‘über den R[hein]’ even be interpreted literally in the sense of Seybold surpassing Rembrandt? No doubt, as court painter, Seybold eclipsed the Dutch master’s social status, and perhaps he also overshadowed Rembrandt with his hitherto highly admired neat handling of paint.

While the Self-Portrait can be enjoyed without any background knowledge, it can only be fully appreciated after comparing the fictional motifs in the painting with historical reality. Only this particular day’s issue of the Wienerisches Diarium could have offered Seybold the unique opportunity to illustrate both his emulation of Rembrandt and the achievement of his professional pinnacle. By relating the contents of the newspaper to a source of inspiration and the stage of his career, he created a highly personalised iconography. It remains unclear for whom this self-portrait was originally intended, but most likely the individual in question was a well-informed art lover, who was a connoisseur of both Seybold and Rembrandt.14

42

Christian Seybold

Selfportrait with the 'Wienerisches Diarium' [Viennese newspaper] of 1745, after 26 May 1745

Budapest, Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, inv./cat.nr. 53406

43

Left: Christian Seybold, Detail Self-Portrait fig. 42; Right: Rembrandt, Self-Portrait with shawl, Etching, state II, 135 x 106 mm, Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, inv.no. A 40373

44

Left: Rembrandt, Self-Portrait as Paul (fig. 34); Right: Self-Portrait (fig. 42)

45

Left, from top to bottom: Painted title ‘Wienerisches Diarium’ dated 26 May 1745, flanked by the Habsburg double eagle (detail fig 42); Title of the actual ‘W.D.’ with Maria Theresa’s coat of arms from the edition of 26 May 1745; Title of the ‘W.D’ with the Habsburg double eagle from the edition of 18 September 1745; Right: Page 4 of the ‘W.D’ of 26 May 1745

46

Detail of the palette (fig. 42)

47

Details of both the painted (fig. 42) and the actual newspaper’s passage

Notes

1 Garas 1981, p. 122. In fact, she is describing an artist’s emancipation process from pictor vulgaris to pictor doctus.

2 Mader-Kratky et al. 2019, pp. 102-105.

3 This was the central theme of my lectures for the congresses Collecting Dutch and Flemish Art in Germany 1600-1900, The Hague, October 2018 (see Ruhe 2019) and XII Annual Convention of the Austrian and Central European Centers, Vienna 2019. See Ruhe 2022, pp. 47-70. See also: Ruhe 2020, pp. 151-175.

4 Hagedorn 1755, p. 337. Three years later, this passage was translated in a German magazine: ‘Seine Bildnisse, sagt der Herr Verfasser [Hagedorn], werden durch die Art, womit er sie zu historiiren weis, zu wahren Gemälden’. Nicolai/Mendelssohn 1758, p. 300.

5 Hagedorn 1762, p. 276.

6 Richardson 1725, pp. 13-14: ‘[…] to sit for one´s Picture, is to have an Abstract of one’s Life written, and published […]’; Sulzer 1774, vol. 2, p. 921.

7 Van de Wetering 2005, no. 24, 549. As Rembrandt’s role as Paul was only recognised in 1919, programmatic allusions to Paul are absent in Seybold’s portrait.

8 ‘De gekromde winckbrauwen, vertoonen verwonderinge, en in der waerheyt, soo geeft sich de Schilder tot sulcke nauwe en scherpsinnige doorsnuflingen van de alderminste dingen in sich self, en dat door de hulpe van de konst, dat hy daer lichtlijck verbaestheydt en swaermoedigheydt van krijght’. [The curved eyebrows show wonder, and in truth, the Painter thus gives himself to such close and astute examination of the least things in himself that through the aid of art, he gets light astonishment and melancholy.] Ripa/Pers 1644, p. 452. Other authors also described this feature in their art theoretical treatises as a motif for expressing the thought process: ‘Een rimpelagtig Voor-Hoofd geeft meest altijd d’overdenking van veel groote dingen te kennen’. [A frowned forehead is usually an expression of deep thinking.] Goeree 1704, p. 107.

9 Both reports mention preparations for combat during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748), which erupted after the death of Emperor Charles VI (1685-1740), on 20 October 1740. The item of 11 May 1745 reports on the run-up to the infamous Battle of Fontenoy that would take place later that day. Austria and her allies were defeated by the French army, led by Maurice of Saxony (1696-1750), half-brother of Elector of Saxony and Polish King Friedrich August II.

10 [With Royal], [the new me], [has just arrived].

11 Mader-Kratky et al. 2019, p. 105, 106.

12 Van Mander 1604, p. 79v: ‘Noch is t’Aenmercken en te houden in ghedacht, dat alle dees costlijcke stucken alleen maer ghemaeckt en waren met vier verwen’. [It is remarkable and should be acknowledged that all these priceless pieces were only made with four colours of paint.]

13 Sandrart 1675-1680, vol. 2, Buch 3 (niederl. u. dt. Künstler), p. 326: ‘Rembrand von Ryn’; De Piles 1699, p. 433; ed. 1715, p. 421: ‘Rambran van Rein’; German transl.: De Piles 1710, p. 512: ‘Rembrand van Rein’.

14 A more extensive contribution about this portrait is due to be published in Bulletin du Musée Hongrois des Beaux-Arts, autumn 2021.