5.2 Comparison with other Bohemian Art Collections

Netherlandish art was popular with Central European collectors, who were undoubtedly influenced by the famous collection of Emperor Rudolf II (1552–1612) in Prague and by other prominent galleries such as the one founded by Leopold Wilhelm I of Austria (1614–1662) [4]. In general, Bohemian collectors were fond of history paintings, but also of landscapes, hunting scenes as well as still lifes, all suitable for cabinet rooms. During the second half of the 17th century they built new grand Baroque palaces that needed to be filled with large collections of art. Their collecting practice differed from the earlier concept of the cabinet of curiosities.1 A picture gallery was part of the collector’s self-representation and expressed his social status and financial situation.2 The collector could show off his exquisite collection to visitors and guests, thus making the gallery a place for socializing as well. Collectors were competitive and tried to outshine each other by building grand collections. Even though they saw their collection as a ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’, collectors also appreciated artworks individually, be it from the past or from the present.

As indicated above, the city of Prague had close ties with the Imperial court in Vienna and Brussels. Some collectors from Prague also had close relationships with the Netherlands. Bohemia experienced a growing economic prosperity after the Thirty Year’s War.3 Aristocrats from the region gradually became more involved in the world of artistic patronage. They came into contact with art and architecture during their Grand Tours and diplomatic missions through Europe, which enhanced their artistic taste and connoisseurship. In 1647, during his Grand Tour, Count Humbrecht Johann (Jan) Czernin (1628-1682) [5] saw the collection of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in Brussels. Afterwards, Czernin installed an impressive collection in his city palace in Prague. He added works by Brueghel, Floris, Rembrandt, Rubens and Van Dyck, among others, to his collection.4 His descendants purchased more Dutch and Flemish art, including Flemish tapestries and they had their portraits painted by painters of Netherlandish origin.

Nostitz's gallery was the largest art collection in Prague and consisted largely of Dutch and Flemish paintings. It was founded by Johann Hartwig Nostitz-Rieneck (1610–1683), Lord Chamberlain of Bohemia; at the time of his death, his collection consisted of 350 pictures which were kept at his palace in Prague and in Falknov (Sokolov/ Falkenau).5 Only a small portion of the collection has been identified. His son, Anton Johann Nostitz-Rieneck (1652–1736) acquired more pictures for the collection. However, the largest addition to the collection was the inheritance of the impressive art collection of Count Nostitz’s childless half-brother František Antonin Berka z Dubá (1649–1706) in 1706, who had been a governor and hereditary grand marshal of Bohemia.6 Count Berka acquired Italian pictures during his time as a diplomat and from 1670 onwards he bought primarily Netherlandish art.7 There are several (partial) inventories of the Berka collection known.8 In 2012, an analysis of the different genres in the Berka collection was made based on a 1692 sale inventory which was drawn up the collector to sell 239 pictures to Johann Adam Andreas, Prince of Liechtenstein (1657/62–1712).9 It shows that the largest part in the collection consisted of history paintings (33 %), landscapes (23 %) and still lifes (11 %); 15 % were portraits (mostly of unknown sitters) and tronies, while genre pieces accounted for only about 3 % of the total.10 Like the Wrschowetz collection, the Berka collection contained relatively many history pieces: this genre, especially mythological subjects, was loved by aristocratic collectors and ranked highest in the genre hierarchy. Another interesting distinction can be seen in the presence of genre pieces in the two collections; Wrschowetz owned significantly more genre pieces (13%) than Berka. This clear preference for still lifes and genre pieces suggests that Wrschowetz followed his own taste when acquiring artworks.

Since Wrschowetz and Anton Johann Nostitz were friends, it seems likely that Wrschowetz was influenced by his collection, and probably also by other German or Central European collections. Although he could not compete with Nostitz's collection in terms of size, the symmetrical arrangement of the collection might have been a way to distinguish himself and strengthen the collection as a whole. The collection of Elector Lothar Franz von Schönborn (1655–1729) was considered as one of the greatest in South Germany [6]. It is not known to what extent these collectors had an interest in symmetrical arrangements like Wrschowetz, but Elector Franz Lothar von Schönborn placed his paintings according to the latest fashion.11

Bohemian collectors could obtain paintings from Flemish art dealers who were active in the region. The Forchondt family from Antwerp, for instance, had a branch in Vienna and belonged to the most important art dealers of their time, other dealers active in Vienna were Jan Vlooitz, Bartholomeus Floquet (c. 1645-1690) and Fransiscus de Neve II (1632-after 1704).12 Renowned collectors such as Count Humbrecht Jan Czernin, Johann Hartwig Nostitz (1610–1683) [7], Prince Johann Adolf von Schwarzenberg (1615–1682) and Franz Anton Berka von Dubá acquired paintings from the Forchondt firm. Apart from Vienna, Prague had a good market for paintings. The dealer Guilliam van de Cruys (Creutz) (1628-1672) had his shop based in Prague. Art dealers not only sold imported pictures from the Low Countries but also from local contemporary artist.13 Possibly, Wrschowetz acquired his first paintings from the art agent and painter Johann Spillenberger (c. 1628-1679); he was based in Vienna and the son-in-law of the dealer Melchior Lidl who moved his dealership from Augsburg to Amsterdam in the 1670s. Wrschowetz had three paintings by Spillenberger in his collection. Furthermore, the painter-dealer sold mainly paintings by Netherlandish and German artists which fits within Wrschowetz’s collection; he had pictures by the following German artists in his collection: Hans von Aachen (1552-1615), Heinrich Aldegrever (1502-1555), Johann Michael Bretschneider, (1680-1729), Hans Burgkmair I (1473–1531), Lucas Cranach (1473-1553), Matthäus Gundelach (1566-1654), Johann Heiss (1640-1704), Johann Philip Lemke (1631-1711) and Johann Heinrich Schönfeld (1609-1684). Among Spillenberger’s clients were many Bohemian collectors, e.i. from the Czernin, Nostitz and Berka families.

4

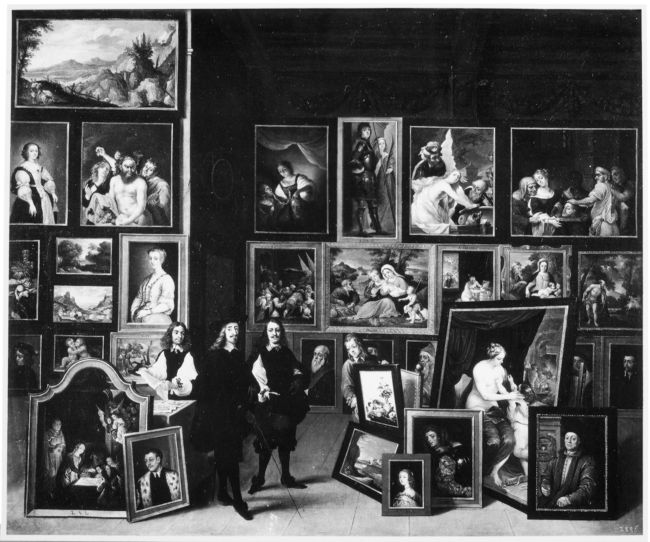

David Teniers (II)

Portrait of Leopold Wilhelm, Archduke of Austria (1614-1662) in his Brussels gallery of paintings, 1650s

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Lázaro Galdiano, inv./cat.nr. 8447

5

Karel Škréta

Portrait of Humprecht Johann Count Czernin of Chudenice (1628-1682), before 1660

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. 19123

6

Arnold Boonen

Portrait of Lothar Franz von Schönborn (1654-1729), Elector of Mainz, c. 1694-1695

Mainz, Landesmuseum Mainz, inv./cat.nr. 305

7

Karel Škréta

Portrait of Count Johann Hartwig Graf Nostitz-Rieneck (1610-1683), dated 1672

Kladruby, Kladruby Monastery

Notes

1 The cabinet of curiosities or Kunstkammer developed alongside the picture gallery as a separate room. Seifertová 2015, p. 17.

2 Seifertová 2015, p. 19.

3 Fornasiero 2017, p. 114.

4 Mzykova 2012, p. 19.

5 Bubryák 2018, p. 107.

6 Franz Anton Berka von Dubá was a diplomat for thirty years and served at varies courts in Europe (Denmark, Sweden, Hamburg, France, Holland); the majority of his diplomatic services were in Rome and Venice. During his diplomatic journeys he commissioned local artists: in The Hague he commissioned a portrait bust by Jan Blommendael (1636-1707) (currently in the Jablonné v Podještědi). Bubryák 2018, p. 116.

7 Count Berka purchased 92 paintings from the Forchoudt art dealers. The purchases made by Count Berka were annotated by Slavíček 1983, p. 227–231.

8 Count Berka kept 105 pictures at his castle in Nový Falkenburk (Neufalkenburg), where an inventory was drawn up in 1694 and he inventoried his paintings at his estates in Jablonné v Podještědi (Deutsch Gabel) and Nemyslovice (Nemyslowitz) in 1706. Published in: Slavíček 1995, Appendices I, II. Berka displayed a part of his collection in his summer palace in Josefstadt (Vienna) that once belonged to Count Maximilian Anton von Salla. Slavíček 1996b, p. 509. See for more on the Berka collection: Bubryák 2018, p. 116-118.

9 Haupt 2012, p. 538-544.

10 Bubryák 2018, p. 28. The Berka collection was compared to the Esterházy inventory dated from 1669 and Dutch inventories between 1630-1649. See table 1 in Bubryák 2018, p. 27.

11 Von Horst 1967, p. 162.

12 Bubryák 2018, p. 112.

13 Bubryák 2018 p. 112.