3.5 Reconstruction of the Hanging

Unfortunately, no drawn hanging plans or the like have been found so far to give us an idea of the historical presentation. To reconstruct the original hanging of the paintings, we have to rely on inventories and the first printed catalogue from 1783. In the preliminary report, the author Simon Causid wrote (in translation), ‘[t]o indicate all of them in sequence, as they follow one another in the rooms, so that they can be easily found according to the information and the register’.1

Consequently, the following reconstruction shows the situation at the time of Landgrave Friedrich, which, however, can still largely be traced back to his father. However, Engelschall (the first biographer of Johann Heinrich Tischbein I (1722–1789) mentions that the court painter under Landgrave Friedrich had been involved when the gallery was (in translation) ‘more tastefully furnished’.2 Unfortunately, Engelschall did not mention exactly what these changes looked like. The paintings hung on the long walls in several registers one above the other.3 On the wall facing the street, the Time-of-Day Cycle by Claude Lorrain (1604/5–1682) (now in St. Petersburg) and Adriaen van der Werff’s (1659–1722) Four Seasons (burned in Kassel in 1941), as well as counterparts by other artists, resulted in a rhythmic structuring of the walls, over which the large-format main works were regularly arranged [18].

At the center hung Rubens’ large painting Mary with Jesus and John, Venerated by Repentant Sinners and Saints (inv. no. GK 119), under David Teniers’ The ‘Oude Voetboog’ Guild on the Grote Markt (today St. Petersburg, Hermitage).4 To the right and left were two works by Rembrandt depicting women as counterparts: A Bohemian Princesse (today Ferdinand Bol, inv. no. GK 238) and A Woman who is Caressed by her Child (lost).5 Another work by Rembrandt — the Descent from the Cross, which was highly praised in the 18th century (today St. Petersburg, Hermitage) — hung a little further to the right.6

18

Picture Gallery of Wilhelm VIII. of Hessen-Kassel, Reconstruction of the hanging, wall towards the street

19

Picture Gallery of Wilhelm VIII. of Hessen-Kassel, Reconstruction of the hanging, wall towards the court

22

Rembrandt

Jacob blessing Manasseh and Ephraim, dated 1656

Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel), inv./cat.nr. GK 249

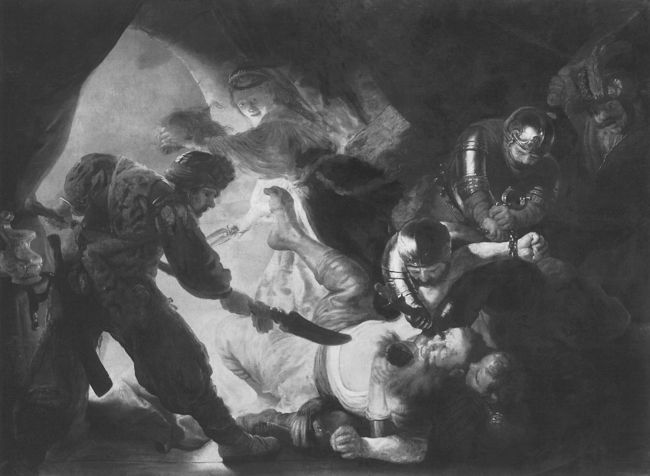

21 (lost in World War II)

studio of Rembrandt

The blinding of Samson (Judges 16:21), ca. 1636

Kassel, Museum Schloss Wilhelmshöhe, inv./cat.nr. GK 252

23

after Rembrandt

The standard-bearer, after 1636

Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel), inv./cat.nr. GK 251

22

attributed to Willem Drost

Man in armour, 1650-1659

Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel), inv./cat.nr. GK 245

However, a total of 17 works by Rembrandt (or believed to be his) were presented on the wall facing the courtyard and thus had the best light in the room [19]. They were arranged around the central large formats by Jacob Jordaens’ The twelfth Night (inv. no. GK 108) and Teniers’ Peasant Dance (inv. no. GK 148) and were grouped together. This clearly shows the formation of the counterpart as an organizing principle. The Jacob’s Blessing [20] on the left found its counterpart in the Blinding of Samson [21] on the right.7 Besides the similar format, there is also a connection in terms of subject matter: in the two biblical histories, ‘seeing’ is shown in opposing themes. While Samson is forcibly robbed of his eyesight, in Jacob's case it is the result of his old age. However, he sees with his inner eye the future of his two grandchildren and then makes his decision to bless one of them. Seeing and non-seeing are brought into an antagonistic relationship. A similar ordering principle can also be discerned in the portraits and half-length pictures. The thoughtful man in armor [22] on the right responds to the standard bearer, ready to fight, on the left [23].8 Both paintings were acquired together in 1755, perhaps with the intention of presenting them as counterparts. The contrasts created enhanced the effect of the individual paintings in an incomparable way.9 Thus Wilhelm's gallery became a sophisticated system of staged hanging, which no longer followed merely decorative principles, but also aimed to do justice to the individual works of art.

Epilogue

With the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War, further work on Wilhelm’s gallery project came to a halt. Nevertheless, the existing gallery attracted many visitors and helped to make Kassel a mandatory stopover for art lovers on the continent.10 The competition with Dresden is evident in a letter from Wilhelm to his friend Baron von Häckel of June 1753 about a painting by Raphael that was sold for 2,500 ducats to Friedrich August in Dresden (in translation): ‘I wished that the Englishman in Dresden had brought his piece by Raphael to me. Admittedly, the price is very high, but if it is so beautiful and good, I would have gone beyond that’.11 This coincides with Wilhelm’s plan to create a separate space for Italian paintings next to the existing gallery. At the end of October 1753 he wrote to Häckel (in translation): ‘I am gradually getting the necessary material for a gallery of Italian pieces, and I believe that there is not much missing. If only the building was there for it’.12 That same year, August Friedrich managed to acquire one of Raphael’s masterpieces, the Sixtine Madonna for 25,000 Roman scudi, which is about 75,000 guilders and thus much more money than Wilhelm had spent in total for the Röver cabinet.13 So Wilhelm probably knew that in the case of Raphael he could not compete with Dresden or Düsseldorf, but with Rembrandt he could. It is Netherlandish art in particular that Wilhelm was able to collect on a high level and scale. Until today, Rembrandt is one of the leading stars of the collection in Kassel.

Notes

1 Causid 1783, Vorbericht.

2 Engelschall 1797, p. 46.

3 Lange/Trümper 2012, pp. 84–91.

4 Oil on canvas, 135 x 185 cm, St. Petersburg, Eremitage, Inv. II, Nr. 572. See: Eissenhauer et al. 2008, pp. 248–249.

5 Weber et al. 2006, pp. 78–84.

6 Lange/Trümper 2012, pp. 90–91.

7 Weber et al. 2006, cat. nos. 30 and 32.

8 Weber et al. 2006, cat. nos. 33 and 34.

9 Weber et al. 2006, pp. 47–64.

10 Linnebach 2014, pp. 241–252.

11 ‘Ich wollte daß der Engelländer zu Dresden sein Stück von Raphael hierhergebracht hätte. Der Preiß ist zwar sehr hoch, wenn es aber so schön und guth ist, so wäre da auch noch über hinausgekommen'. Drach 1888, p. XLI.

12 ‘Ich erhalte allmählig den nöthigen Stoff zu einer Galerie von Italiänischen stücken und Ich glaube, daß mir soviel nicht mehr daran fehlet, wan nur das Gebäude darzu auch da wäre'. Drach 1888, p. LXVI.

13 Brink 2012, pp. 69-73.