3.1 34 Rembrandts for Kassel

Unfortunately, our records of the collection's acquisition are incomplete. Previous owners are only rarely mentioned in the inventory. But of some works we do have information on prices that can at least give us an idea of their former value. Mostly, Wilhelm bought works by Rembrandt at auctions, through art dealers or collectors in the Netherlands and Germany. At least one work by Rembrandt, however, was bought from an Italian collector.1

Well-known is the purchase of a cabinet of 64 paintings from the Delft art collector Valerius Röver II (1686–1739): it contained eight works by Rembrandt and was bought for the total sum of 40,000 guilders.2 It was the highest price paid for a collection in the Netherlands in the 18th century.3 On the basis of a simple calculation, each Rembrandt would have cost 625 guilders. Was this a reasonable price for a Rembrandt? Following Koenraad Jonckheere’s database, the average price for a Rembrandt in an auction between 1676–1739 was 140 guilders.4 Within the 124 works analyzed by him, the lowest price was 0 guilders for unsold paintings, the median was 47 guilders and the highest price was 2,510 guilders. Consequently, 625 guilders does not sound cheap but neither too expensive.

2

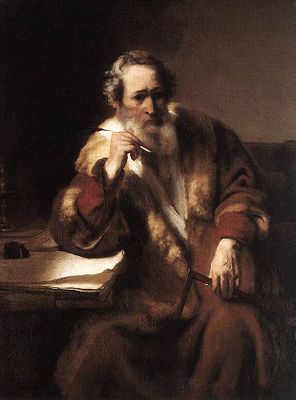

follower of Rembrandt

Bust of an old man, c. 1645

Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel), inv./cat.nr. GK 247

Of the 34 Rembrandts in Kassel, we know the prices for 15 of them: 20 guilders was paid for a small tronie [2],5 160 for a half-length portrait [7],6 735 for a small scale biblical subject [3]7 up to 1,100 guilders for one of his rare full-length portraits [4].8 Can we figure out a precise strategy in Wilhelm’s acquisitions? Was he only looking for bargains or did he choose based on personal preference and taste? By looking at works that Wilhelm could have acquired but which he chose not to buy, we can discover more about Wilhelm's financial considerations. At the auction of the collection of Theodoor Wilkens (1690–1748) in Amsterdam, for example, he bought four paintings by Italian masters (Michele Rocca [1670–1751/1771], Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari [1654–1727] and Francesco Trevisani [1656–1746]) for the total amount of 1,035 guilders, but not the Portrait of a Woman by Rembrandt which was sold for only 88 guilders.9 In this case, the price was clearly not the decisive reason. Other examples show that Wilhelm benefited from a tight network of advisors to build his collection. This network consisted of collectors such as Baron Heinrich Jakob von Häckel (c. 1682–1760) in Frankfurt and the painter Philip van Dijk (1683–1753).10 Furthermore, officials in the service of Wilhelm acted as his advisors, including General von Donop, who was sometimes jokingly called ‘General director of my eye’s delight’11, and the court painter and gallery inspector Johann Georg Freesen (1701–1777).12 Another group — and probably the most important one — was a circle of collector-dealers in the Netherlands, such as Antoni Rutgers (1695–1778), Gerard Hoet II (1698–1760), Govert van Slingelandt (1694–1767) and Willem Lormier (1682–1758).13 Finally, Gerhard Morell (1710–1771) in Hamburg and Count Francesco Algarotti (1712–1764) in Venice should be mentioned, both of whom also advised other German princely collectors.14

One of the 34 Rembrandt paintings must have been bought before 1730, as the work [5] is already included in the inventory of the so-called ‘New Cabinet’ in the Palace of Wilhelm’s father Landgrave Karl I von Hessen-Kassel (1654–1730).15 It hung there with paintings by other artists, such as Antonio Molinari (1655-1704), considered at the time to be a work by Antonio Zanchi, and Flemish portraits attributed to Abraham de Vries (1590-1649/50), among others.16 As for paintings, it is difficult to discern a specific collecting strategy for Landgrave Karl.17

Wilhelm was the sixth son of Landgrave Karl and spent a long time in the Netherlands in the service of the General states army, being governor of the fortresses in Breda and later in Maastricht.18 From an early age, he was interested in painting. He spent much time in Kassel helping his old father from the 1720s onwards. After Karl’s death in 1730, Wilhelm became governor for his elder brother Friedrich (1676-1751) who himself became King of Sweden after his marriage to princess Ulrika Eleonora (1688-1741) while keeping his position as the ruling landgrave of Hessen-Kassel. Was the first Rembrandt painting in Kassel in the cabinet of his father maybe in fact acquired by Wilhelm? Either way, after 1730 he incorporated a good number of works of his father’s collection into his own picture gallery, including the Rembrandt.19 It was not until the death of Friedrich in 1751 that Wilhelm became Landgrave of Hessen-Kassel. This point is important because until then, considerable sums (around 225,000 thaler or 450,000 guilders) had been sent to Sweden every year. The total income of the state from taxes and subsidies was 1,450,000 thaler; about 16 % of the state money was sent to Wilhelm’s brother in Stockholm.20 Although these numbers are only estimations, they do indicate that Wilhelm's new position as reigning landgrave from 1751 onwards enabled him to spend even more money on art. In a letter from May 1751 to Baron Häckel, Wilhelm complained (in translation): ‘I have to deal with so many things, to acquire and pay so much that I do not know where to turn my head’.21 Obviously, it is not by chance that the most expensive Rembrandts — as far as we know — entered Wilhelm’s collection in 1752: The Holy Family with the Curtain cost 735 guilders and the full-length Portrait of Andries de Graeff 1,100 guilders.22

3

Rembrandt or studio of Rembrandt

Holy Family, dated 1646

Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel), inv./cat.nr. GK 240

4

Rembrandt

Portrait of Andries de Graeff, 1639

Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel), inv./cat.nr. GK 239

5

follower of Rembrandt

Bust of a man wearing a golden chain with a cross, before 1731

Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel), inv./cat.nr. GK 231

But let us turn back to the earlier acquisitions. It is certain that Wilhelm bought the famous Apostle Thomas (’The Architect’) by Nicolaes Maes (then believed to be by Rembrandt) [6] at the auction of the collection of Lambert ten Kate (1674–1731) in Amsterdam on 16 June 1732.23 Unfortunately, we do not know how much Wilhelm spent on it. In 1738 he bought the Portrait of Jan Harmensz. Krul from the art dealer Antoni Rutgers for 160 guilders which is the first known price for a Rembrandt in Kassel [7]. Given Jonckheere's data and his calculation of an average price of 140 guilders for a Rembrandt, the amount of Wilhelm's purchase seems quite reasonable.

Compared to the prices previous owners had paid for the painting, Wilhelm even had a bargain. In 1735, the painter Philip van Dijk sold the portrait for 200 guilders to the collector Valerius Röver. Three years later, in 1738, Röver sold it to the art dealer Antoni Rutgers for a lower price of 165 guilders. So within three years, the value of the painting dropped from 200 to 160 guilders, a decrease of 20%.24 Interestingly, Rutgers mentioned the price drop in a letter to Wilhelm explaining that his purchase would be really cheap.25 Furthermore, Rutgers explicitly offered this painting as a companion piece for a portrait by another artist already in Wilhelm’s possession: Anthony van Dyck’s Portrait of Lucas van Uffelen, today in New York [8].26 Other works offered by Rutgers also meant to be pendants to paintings that Wilhelm already had in his collection. The contact between dealer and collector followed a clear strategy.27 With this tactic, Rutgers was able to sell several paintings to the landgrave. It is not unconceivable that he added the 5 guilders that he had lost with the transfer of Rembrandt’s Portrait of Jan Harmensz. Krul to another acquisition.

6

attributed to Nicolaes Maes

The apostle Thomas, dated 1656

Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel), inv./cat.nr. 246

7

Rembrandt

Portrait of a man, possibly Jan Harmensz Krul, dated 1633

Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel), inv./cat.nr. GK 235

8

Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Lucas van Uffelen l (1586-1638), 1622

New York City, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 14.40.619

Notes

1 Krellig 2017, pp. 263–278.

2 Rehm 2017, pp. 216–225.

3 Korthals Altes 2003A, pp. 157–161.

4 Jonckheere 2008, pp. 229–233. For another analysis of prices of Rembrandt paintings covering a larger period of time: Carpreau 2017, pp. 63–68.

5 Weber et al. 2006, cat. nos. 24–25.

6 Weber et al. 2006, cat. no. 7.

7 Weber et al. 2006, cat. no. 29.

8 Weber et al. 2006, cat. no. 27.

9 Schnackenburg 1996, pp. 81–82 (Chiari), 250 (Rocca) and 298 (Trevisani). Weber et al. 2006, p. 46 (Rembrandt).

10 On Häckel: Svenningsen 2016, pp. 410–422. On van Dijk: Korthals Altes 2003B, pp. 34–56. Korthals Altes 2003A, pp. 126-148.

11 Drach 1888, p. XLVIII.

12 On Donop: ‘Donop, August Moritz Abel Plato von‘, in: Hessische Biografie [15 April 2021]. On Freesen: AKL, vol.44 (2005), p. 328.

13 Korthals Altes 2000/2001, pp. 251–311. Korthals Altes 2003A, pp. 149–175.

14 On Morell: North 2012. On Algarotti: Krellig 2017.

15 Weber et al. 2006, cat no. 3. Ševčík 2019, pp. 173–175.

16 Dohe et al. 2018, pp. 308–311.

17 Dohe et al. 2018, pp. 75–84.

18 Schnackenburg 1991.

19 Lange 2017, pp. 215–229.

20 Both/Vogel 1964, p. 40.

21 ‘Ich habe jetzt so viel zu handeln, zu kaufen und zu bezahlen, daß ich nicht weiß, wo ich den Kopf wenden soll.’; Drach 1888, p. LX. Both/Vogel 1964, p. 144.

22 Weber et al. 2006, cat. nos. 27 and 29.

23 Weber et al. 2006, cat. no. 6.

24 Weber et al. 2006, cat. no. 7.

25 Drach 1890, pp. 201–202.

26 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436253 [14 November 2021].

27 Drach 1890.