10.3 Dutch and Flemish Paintings

In his acquisitions, Josef Hoser concentrated on paintings by Dutch and Flemish masters as well as on the ‘later German schools emerging from them’:1 he collected works from the 17th century to the present day. According to current attributions, there were 49 Dutch paintings and 44 Flemish paintings in the Hoser collection. Hoser was proud to own 35 paintings from the famous collection of Count Moritz von Fries (1777–1826) in Vienna.2 Around 1800, Moritz von Fries had been one of the wealthiest men in Austria due to the banking house Fries, but his fortune was lost in the following 20 years and the collection was sold in several auctions.3 A good provenance was a sign of quality for Hoser. Thus, prints after paintings served as a kind of ‘impact factor’ of the artwork, testifying to its authenticity and excellence.4 Although all genres of painting were represented in the collection, there was an emphasis on landscape and genre painting.

Undoubtedly the most famous work from the Hoser Collection is Arent de Gelder’s (1645–1727) Vertumnus and Pomona [6].5 It was then considered as a work by Rembrandt (1606–1669) and had previously been in the collection of Count Fries. Hoser also owned the print of Bernard Lépicié (1698–1755) after the painting, on which it is attributed to ‘Rembrandt’. Interestingly, he mentions that at the end of the 18th century (1797–1798), the painting was registered under the name of Arnold de Gelder in the collection of Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun (1748–1813).

Hoser acquired several important works from the Fries collection, for example, the four small pictures of a five-senses series by Adriaen van Ostade (1610–1685). The sense of sight is missing in the series, which Hoser originally interpreted as a sign that ‘sight’ should be embodied by the observer himself [7-10].6 Thematically exceptional is a picture by Jan Steen (1626–1679), showing a charivari during carnival [11].7

6

attributed to Arent de Gelder

Vertumnus, in the guise of an old woman, wooing Pomona, c. 1700

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 112

7

Adriaen van Ostade

The Sense of Smell (from a series of the Five Senses), c. 1650

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 158

8

Adriaen van Ostade

The sense of Hearing (from a series of the Five Senses), c. 1650

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 182

9

Adriaen van Ostade

The Sense of Taste (from a series of the Five Senses), c. 1650

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 144

10

Adriaen van Ostade

The sense of Touch (from a series of the Five Senses), c. 1650

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 157

11

Jan Steen

Nocturnal serenade, c. 1670-1679

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 253

12

Gabriel Metsu

Young woman selling fish to an old woman, c. 1656-1658

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 125

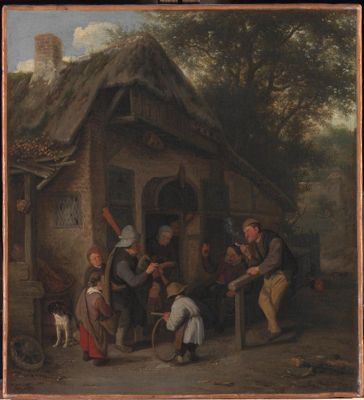

Hoser obtained some important works from the collection of Freiherr Johann Baptist Puthon (1776-1839) in Vienna, including two fine genre paintings. The Woman Selling Fish by Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667) was probably bought quite late, because it first featured in the catalogue of 1844 [12].8 The other painting is the Bagpiper in front of a Farmhouse by Cornelis Dusart (1660–1704) from 1686 [13].9 A late but major acquisition from the Puthon collection was a huge painting by Gerbrand van den Eeckhout (1621–1674) depicting Eliezer and Rebecca at the Well (Genesis, 24:17) [14].10 He must have bought it in late 1844 or in 1845, because it is not mentioned in the catalogue of his collection in Prague from 1844. Additionally, Hoser obtained an evening landscape by Aert van der Neer (1603–1677) from the same source, showing the rarely depicted topic of a game of Kolf on a course, and not on ice [15].11 Another painting from the Puthon collection was Road through the Woods by Guillam Du Bois (1623/5–1680) [16].12 A late, impressive landscape by Pieter de Molijn (1595–1661) from 1653 [17]13 and a beautiful landscape by Herman Saftleven (1580–1627) [18] were both aqcuired from other collections.14

13

Cornelis Dusart

Bagpiper and audience in front of a peasant house, dated 1686

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 136

14

Gerbrand van den Eeckhout

The meeting of Rebekah and Eliezer at the well, c. 1660-1665

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 199

15

Aert van der Neer

Evening game of kolf in a Dutch village, dated 1649

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 123

16

Guillam Du Bois

Forest landscape with a rider on a gray

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 154

17

Pieter de Molijn

Hilly landscape with walkers and travelers on the way, dated 1653

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O-151

18

Herman Saftleven

Mountainous landscape with a river in the depths, 1640's

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 209

19

Allaert van Everdingen

Norwegian landscape with a fjord

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 117

Hoser was also a geologist and, occasionally, his interest in art reflects this. On a painting by Allaert van Everdingen (1621–1675) of a Norwegian Fjord he thought he could determine the solid rock as gneiss merging with mica schist [19].15 Hoser also owned numerous Flemish paintings, amongst other by Joos de Momper II (1564–1635) [20],16 David Teniers II (1610–1690),17 Frans Snijders (1579–1657),18 David Rijckaert (1612–1661),19 Pieter van Bloemen (1657–1720)20 and Lodewijk de Vadder (1605–1655).21 All these paintings are among the best of the collection. Of course, he also owned less important works and several paintings are today considered copies or imitations.

20

Joos de Momper (II)

Mountainous landscape with hermits

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 117

Notes

1 For a definition of ‘Nachwirkung’, see Van Leeuwen 2013.

2 Hoser 1846, p. VI.

3 G. Otruba, ‘Fries, Moritz Graf von’, in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 5 (1961), p. 606; https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd13213571X.html#ndbcontent

4 Hoser 1846, pp. VII-–VIII.

5 Hoser 1846, p. 138–141. Ševčík/Bartilla/Seifertová 2012, pp. 154–155, cat.no. 129.

6 Hoser 1846, pp. 128–129. Ševčík/Bartilla/Seifertová 2012, pp. 322–325, cat. no. 308–311.

7 Hoser 1846, p. 160. Ševčík/Bartilla/Seifertová 2012, pp. 417, cat. no. 409.

8 Hoser 1844, p. 18. Hoser 1846, p. 104. Ševčík/Bartilla/Seifertová 2012, pp. 266–268, cat. no. 244.

9 Hoser 1846, pp. 53–54. Ševčík/Bartilla/Seifertová 2012, p. 136, cat. no. 112.

10 Hoser 1846, pp. 56–57. Ševčík/Bartilla/Seifertová 2012, pp. 140–141, cat. no. 116.

11 Hoser 1846, pp. 121–122. Ševčík/Bartilla/Seifertová 2012, p. 306, cat. no. 289.

12 Hoser 1846, p. 27. Ševčík/Bartilla/Seifertová 2012, p. 131, cat. no. 108.

13 Hoser 1846, pp. 114–115. Ševčík/Bartilla/Seifertová 2012, p. 290, cat. no. 272.

14 Hoser 1846, pp. 180–181. Ševčík/Bartilla/Seifertová 2012, p. 400, cat. no. 392.

15 Hoser 1846, pp. 62–64: ‘Gneis mit Glimmerschiefer’. Ševčík/Bartilla/Seifertová 2012, p. 146, cat. no. 120.

16 Hoser 1846, p. 117. Slavíček 2000, p. 212, cat. no. 220.

17 Hoser 1846, pp. 164–165. Slavíček 2000, p. 285, cat. no. 327.

18 Frans Snijders, Hoser 1846, p. 64. Slavíček 2000, p. 274, cat. no. 310.

19 Hoser 1846, pp. 56–57. Slavíček 2000, p. 254, cat. no. 283, as ‘attributed to David II Rijckaert’.

20 Hoser 1846, p. 23. Slavíček 2000, p. 76, cat. no. 27.

21 Hoser 1846, p. 166. Slavíček 2000, p. 307, cat. no. 361.