1.2 Electors of the Palatinate

Within the Palatine Branch of the House of the Wittelsbach, the most important acquisitions were made by the electors Frederick II, Otto Henry and Frederick III. The case of Otto Henry (1502-1559) is most fascinating. Even though he seems to have been unsuccessful in his private and political ambitions (he was not elected prince-elector until three years before his death), he remains a major figure in the arts and literature.1

From a young age, Otto Henry was made familiar with European court etiquette. He was part of the delegation that brought Charles V the news of his election. It was in 1522 that he took over the principality of Palatinate-Neuburg, along with his brother Philip. He transformed his residence in Neuburg with the help of talented architects, painters and sculptors. He also financed a tapestry manufacture.2 Sources attest that at least three Flemish weavers were employed there. He entrusted the management to Christian de Roy, a native of Antwerp. Between 1540 and 1544, the Neuburg workshop wove several monumental series designed to glorify Otto Henry and his family. It was only after his wife Susanna of Bavaria, a staunch Catholic, died prematurely in 1543, that he chose to publicise his Protestant convictions.

It is currently impossible to reconstruct the entire inventory of his tapestries. In 1956, Annelise Stemper published the first thorough study on his collection.3 Recent articles by Hanns Hubach have expanded this study and generally shed new light on the collections of the Electors of the Palatinate.4 By examining the sources, we can estimate that Otto Henry owned over a hundred tapestries. The inventories of Neuburg and Heidelberg castles show that his collection rivalled those of most major European courts, both in terms of quality and the diversity of the themes. As of yet, the latter have not been closely examined. In addition to scenes from the Old and New Testaments, the prince owned a Story of Alexander, a Judgment of Paris and a Fall of Troy. Some of the preserved pieces come undoubtedly from his collection as they bear his coat of arms, namely his initials OHS intertwined and his motto ‘MDZ’ (Mit Der Zeit).

Literature also mentions his simplified re-edition of the Los Honores series, the original edition having been produced around 1520 for Charles V by Pieter Coecke van Aelst‘s workshop in Brussels.5 This monumental series of nine highly complex pieces could serve as a real education treatise for princes. The conveyed message can be summarized as follows: if a ruler practices the main virtues, he can overcome the vicissitudes of Fortune, escape Infamy and hope to receive three great moral principles: Glory, Nobility and Honour. Only the Prudence and another section of the tapestry, with Phoebus Apollo [8], have survived.6 Otto Henry’s woven coat of arms is featured at the centre of the upper border. But several elements make us doubt this was a commission, including the coat of arms on the border, because it was clearly executed at a later date. In any case, Otto Henry ordered a full-length portrait of his wife Susanna woven in Brussels in 1533 [9]. Two years later, its counterpart, his own portrait, was completed [10]. He also purchased the woven full-length portrait of his brother Philip, the count Palatine [11].7

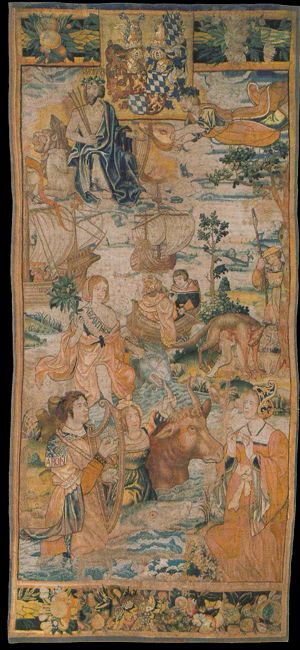

8

Anonymous (Flemish)

The deeds of Fortuna, c. 1530

wool, silk, woven (technique) 383.5 x 177 cm

Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, inv./cat.nr. Gew3946

9

attributed to Jan de Roy (c. 1470) after attributed to Peter Gertner

Portrait of Susanna von Bayern (1502-1543), Pfalzgräfin zu Neuburg, dated 1533

Neuburg an der Donau, private collection Schloss Neuburg an der Donau, inv./cat.nr. T 373

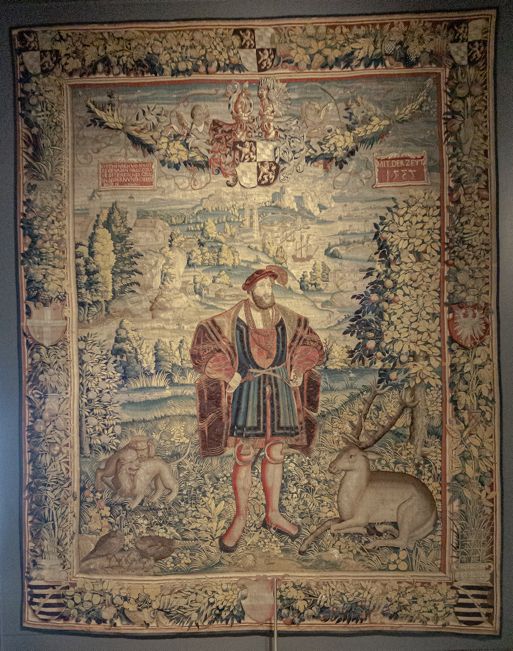

10

attributed to Jan de Roy (c. 1470) after attributed to Peter Gertner

Portrait of Ottheinrich Pfalzgraf zu Neuburg (1502-1559), dated 1535

Neuburg an der Donau, private collection Schloss Neuburg an der Donau

Between 1540-1544, the prince had at least nine series woven in his manufacture, including two sets dedicated to the ‘Journey to the Holy Sepulchre’.8 These tapestries are reminiscent of Otto Henry’s visit to Jerusalem in 1521, where he was knighted. In 1543, he paid for a set on the Siege of Vienna by the Turks, which has not survived. Unfortunately, the Neuburg workshop went bankrupt in 1544 because the prince could not pay his weavers any longer.

He enjoyed a lavish lifestyle. Heavily indebted, he witnessed his own provincial towns take power and sell some of his properties. During the Schmalkaldic War (1546-1547), the imperial troops occupied Neuburg castle and the count palatine was placed under Imperial ban by Charles V. Powerless, Otto Henry attempted to make gold through alchemy experiments during his exile (an exile that lasted until 1552), whilst selling his jewellery and ceremonial clothes. These sales allowed him to recover some of his confiscated tapestries. A few years later, he was forced to negotiate the return of his tapestries, this time from the King of France, because the boat carrying the tapestries with Otto Henry’s coat of arms had been captured by the French.9 The remarkable pugnacity he demonstrated in the retrieval of his tapestries shows how much he was attached to them. His attitude also testifies that his precious textiles represented an enormous investment.

In addition to the works listed above, a set of the Seven Planets derived from Georg Pencz’s models must be mentioned [12].10 It does not bear Otto Henry’s coat of arms, initials nor his motto. This series was probably commissioned during his period of exile. As he could not turn to the Flanders, because of the high price of their tapestries, he may have solicited Melchior Grienmann, employed since 1545 as a weaver at the court of his uncle, the Prince-Elector Frederick II, in Heidelberg. Grienmann had previously settled in Nuremberg, a city that had welcomed Pencz, who worked as a court painter, and a city where Flemish weavers came regularly to look for work.11 Grienmann was one of those newly established weavers. This hypothesis, according to which Grienmann produced a tapestry-series for Otto Henry, is attractive but it is not based on archival documents.

In 1556, he was finally given the title of prince-elector, which enabled him immediately to purchase stupendous tapestries from the Southern Netherlands. He acquired scenes from the Old Testament to beautify his new Heidelberg residence. The last work he commissioned was in Brussels, namely a set of eight pieces featuring his family’s coat of arms. His death put an end to the project. The woven pieces were united in one tapestry showing Otto Henry in Prince Palatine attire.12

11

attributed to Jan de Roy (c. 1470) after attributed to Peter Gertner

Portrait of Philipp, Pfalzgraf zu Neuburg (1503-1548), c. 1533-1535

Neuburg an der Donau, private collection Schloss Neuburg an der Donau

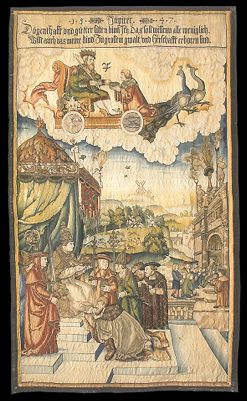

12

possibly studio of Melchior Grienmann after Georg Pencz

The planet Jupiter, dated 1547

Cologny, Fondation Martin Bodmer

Notes

1 Hubach 2002A; Zeitelhack 2002; Ammerich/Harthausen 2008; Seitz 2020.

2 Hubach 2005.

3 See Stemper in Poesgen 1956, p. 141-171.

4 Hubach 2002B; Hubach 2005; Hubach 2010.

5 Delmarcel 2000.

6 Prudentia from a set of the Honours. Woven in Brussels, c. 1530. Wool and silk, 437 x 462 cm. Kurpfälzisches Museum der Stadt Heidelberg. See Stemper 1958; Hubach 2005; Delmarcel 2000, p. 39-40 and 42.

7 See Hubach 2005.

8 Places of the Holy Land. Tapestry design by Matthias Gerund, woven in the workshop of Christian de Roy, Neuburg, 1541. Wool, silk, silver- and gilt-metal-wrapped thread, 480 x 516 cm. Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich (T 3860) and Schloss Neuburg an der Donau (T 374). See Hubach 2005; Goren 2007.

9 See Hubach 2005; Rapp Buri/Stucky-Schürer 2007, p. 75.

10 See Rapp Buri/Stucky-Schürer 2007.

11 Hubach 2015.

12 'GroBer geneaologischer Teppich’. Tapestry woven in Brussels, c. 1557. Wool and silk, 423 x 957 cm. Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich (inv. T 3869). See Hubach 2002B.