7.1 The Rising Popularity of Small-Format Netherlandish Paintings

Sometime in the 1730s, Gerard Hoet II (1698–1760) and Jacques Ignatius de Roore (1686–1747), two art dealers from The Hague, travelled to the small town of Zaventhem near Brussels.1 They had a particular purpose in going there, because they wanted to buy the altarpiece from the local church and take it back to Holland for resale. The work by the renowned Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), depicted St Martin [1]. Although De Roore and Hoet succeeded in agreeing on a price with the pastor, the transaction ultimately fell through because the locals from Zaventhem got wind of the affair and the peasants furiously resisted the removal of their altarpiece. We can read what happened in De Nieuwe Schouburg der Nederlantsche Kunstschilders en Schilderessen written by Jan van Gool (1685–1763), who was acquainted with both De Roore and Hoet:

‘As soon as our dealers had secretly entered the Church, the piece was taken down from the Altar and placed in a crate, yet while they were thus engaged, they heard some noise outside the Church doors; thereupon the same were bombarded with stones, and some shots were fired. The one began to look at the other in fear and trepidation, and after another loud shot rang out, one of the rebellious peasants climbed the church tower and rang the fire bell. Then the church doors were stormed, and after they had been violently battered open, the angry mob poured in, as if possessed by the Furies of Hell, armed with forks, flails and knives; furious and mad with rage at the pastor, at whom they shouted: “You filthy Jew, we do not want our St Martin dragged off to Holland”’.2

Hoet and De Roore took to their heels and fled back to the United Provinces without the Saint Martin, which hangs in the church in Zaventhem to this day.

Among other things, this story illustrates how difficult it was for art dealers to get their hands on altarpieces by artists like Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) or Anthony van Dyck. Paintings by these masters were highly sought after by collectors in the Holy Roman Empire, France and England, but, like good Italian Renaissance paintings, they were quite rare and hence very expensive. Churches usually clung on to their masterpieces for practical or devotional reasons. Because of the way aristocratic families left their art collections to the eldest son as part of the inalienable family heirloom, paintings in the possession of the aristocracy too, rarely came on to the market again.

In contrast, however, there was a real glut of small-format Netherlandish 17th-century paintings on the market. Foreign collectors may well have regarded these paintings as a good alternative to costly Italian paintings — even the best were still available and could still be had quite cheaply, whereas inferior Italian works could often be very expensive indeed.3

Another contributory factor to the rising popularity of small-format Netherlandish paintings may have been that some collectors were conscious of the fact that altarpieces really did not belong in private collections, and that they could never achieve their full effect once they were out of their original setting. Wilhelm VIII (1682–1760), Landgrave of Hessen-Kassel, who amassed a huge collection of paintings in the mid-18th century, once expressed his views on this. When the Leiden art dealer Pieter Boetens (died 1757) offered him three altarpieces by Anthony van Dyck that came from an abbey near Bruges —The Crowning of Thorns, Pentecost [2] and a canvas depicting John the Baptist and John the Evangelist— Wilhelm refused these paintings because he believed they belonged in a church and not in a picture gallery.4 By no means all collectors shared his scruples. Johann Wilhelm, Elector of the Palatinate (1658-1716), and August III (1696–1763), Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, for example, did their utmost to get their hands on altarpieces by Rubens and Raphael (1483–1520).5

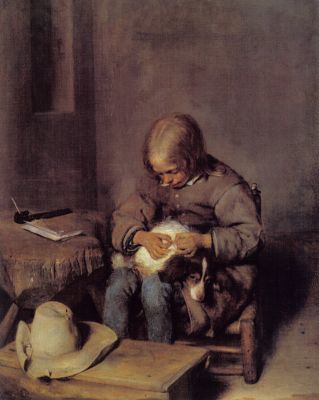

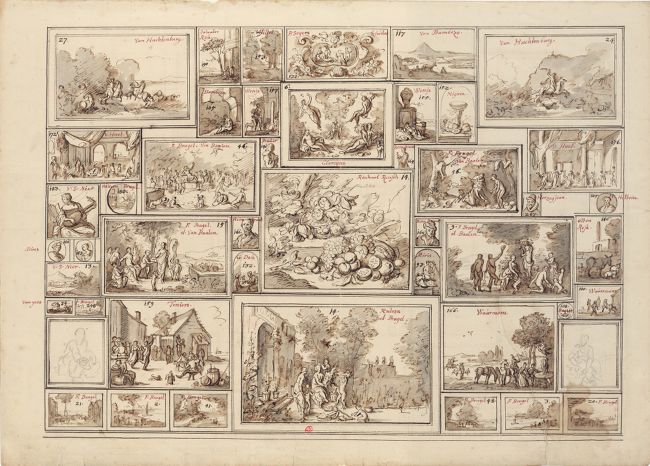

On the other hand, small-format Netherlandish cabinet pictures, called ‘cabinetstucxkens’ in 17th-century Dutch, were considered entirely appropriate by all collectors and were consequently welcome in virtually every collection [3].6 Their private character made them ideally suited for the ‘cabinets’ of paintings that were being formed at this time. In the early 18th century a number of princes in the Holy Roman Empire started work on the building of both galleries and cabinets of paintings. The function of the gallery was to reflect and proclaim its owner’s status, and it was the place for the grander works of art, whereas the cabinets were more intimate affairs, where smaller works of a more private nature would be shown [4].

It is generally agreed that 17th-century Northern-Netherlandish painting was originally intended primarily for the domestic market, and it was not until the end of the 17th century, i.e. after the year of disaster 1672, that it really started to leave the country on a much larger scale. We know very little about the reasons why and the way in which this process of dispersal started. Works by Rembrandt (1606–1669), Cornelis van Poelenburch (1594–1667), Gerard Dou (1613–1675) and Frans van Mieris I (1635–1681) were among the first to cross the border. Later, art dealers started to export the work of many other 17th-century masters. They probably found that the domestic market had become too small and saw new, financially more attractive opportunities abroad —particularly in the Holy Roman Empire, where several rulers were rapidly enlarging their collections. Thus, Netherlandish paintings found their way to the courts in Vienna, Braunschweig, Düsseldorf and Dresden, to name but a few, later followed by Schwerin, Kassel, Potsdam and Karlsruhe as well.

Over the past 15 years, a large number of 18th-century collections in the Holy Roman Empire, owned by both rulers, the nobility and the wealthy middle class, have been (re-)studied in depth.7 The following questions have been researched in particular: Which (type and number of) Netherlandish, German, Italian and French paintings were collected? How and why were they collected, and how were they displayed?8 Apart from these questions, (international) networks of collectors, agents, art dealers, connoisseurs and advisors have been the subject of extensive research.9 German 18th-century sale catalogues have been scrutinized.10 The balance between supply and demand, changes in price and taste, and the differences between theory and practise —i.e., the impact of art literature on the preferences of collectors and vice versa— have been studied.11

The following part of my contribution will address many of these issues by exploring a little-known letter, written on 5 March 1756 by the art dealer Gerard Hoet from The Hague, the one who had failed to acquire the altarpiece by van Dyck in Zaventhem some 20 years earlier. In this letter, he discusses a number of Netherlandish and Italian paintings from the Tallard collection that would come up for sale in Paris later that month. One of his clients, Wilhelm VIII, Landgrave of Hessen-Kassel, had shown an interest in these pictures and asked Hoet for expert advice. The letter offers remarkable insights into the ways in which 18th-century dealers and collectors judged the quality and authenticity of paintings.

1

Anthony van Dyck

Saint Martin of Tours dividing his cloak, 1621 documented

Zaventem (Vlaams-Brabant), Sint-Martinuskerk (Zaventem)

2

Anthony van Dyck

Pentecost: the Holy Ghost descends upon Mary and the apostles, c. 1617-1620

Potsdam, Bildergalerie am Schloss Sanssouci, inv./cat.nr. GK I.10623

3

Gerard ter Borch (II)

Boy de-fleaing a dog, c. 1655

Munich, Alte Pinakothek, inv./cat.nr. 589

4

Jan Philips van der Schlichten

Picture cabinet of Elector Karl III Philipp von der Pfalz-Neuburg (1661-1742) in Mannheim, 1731

Paris, Institut national d’histoire de l'art, inv./cat.nr. MS 409

Notes

1 This contribution is based on Korthals Altes 2003A. I have updated the text and notes, and added new information and insights.

2 Van Gool 1750–1751, vol. 2, pp. 96–97.

3 The famous Parisian art dealer Gersaint explained the popularity of the Netherlandish masters in that way. See E.-F. Gersaint, sales catalogue Quentin de Lorengère (Lugt 590), 2 March 1744, pp. 1–11, esp. p. 6: ‘Comme leurs Tableaux ne sont pas d’un si haut prix, ni si rares que des italiens, c’est de ces Tableaux que sont ornés aujourd’hui presque tous les Cabinets particuliers’ (Because their paintings are not as expensive and rare as the Italian ones, they nowadays adorn nearly all private cabinets).

4 Herzog 1969, p. 36. The works were in the abbey of Ter Duinen near Bruges. Two years later, in 1755, they were purchased for 20000 guilders by Frederick the Great for Sanssouci, his gallery of paintings in Potsdam. See Sommer 1996, pp. 222–223, nrs. 29, 31 and 35. The Descent of the Holy Ghost is the only one of these works not to have been lost during the Second World War.

5 Levin 1905, pp. 211–222. Möhlig 1993, p. 35. Tipton 2006. On the Sixtine Madonna by Raphael, among others: De Chapeaurouge 1993, p. 15.

6 Lammertse/Van der Veen 2017, p. 181 on the 17th-century use of the word ‘cabinetstucxkens’.

7 Among the numerous recent publications, I can only mention a few: Weber et al. 2006; Spenlé 2008; Baumstarck 2009; Seelig 2010; Luckhardt 2014; Jacob-Friesen/Müller-Tamm 2015; Frank/Zimmermann 2015; Windt 2015. Two important publications with the aim of a general comparison of collections in the Holy Roman Empire are North 2002; Savoy 2006 and Savoy 2015.

8 Baumstarck 2009. Gaehtgens/Marchesano 2011. Windt 2015.

9 See, for example, Korthals Altes 2003A; Jonckheere 2008; Jacob-Friesen/Müller-Tamm 2015; Frank/Zimmermann 2015.

10 Ketelsen/Stockhausen 2002.

11 Cremer 1989. Korthals Altes 2011.